In December 2015, Mitleid. Die Geschichte des Maschinengewehrs, or Compassion: The History of the Machinegun, a new production by Milo Rau, premiered at Berlin’s Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz. The production starred Swiss starlet Ursina Lardi – an extremely well-known and critically acclaimed actress[i] – and the Burundi-born, Belgium-based actress Consolate Sipérius. On Wednesday, October 24, 2018, a new version of the production, again directed by Rau, premiered at NTGent[ii]. However, the new production, Compassie. De geschiedenis van het machinegeweer – which also translates to Compassion: The History of the Machinegun – starring the Belgian starlet Els Dottermans – another critically acclaimed and nationally famous[iii] actress – and the French actress Olga Mouak.

Both productions explore questions of white guilt, compassion culture, internalized racism, and the European theatre tradition through extended monologues. Although the productions stand alone and you certainly don’t need to watch one to understand the other, they are also closely connected (and I personally recommend watching both). Compassie acts as a sort of companion piece to Mitleid. Both are border products: theatrical essays exploring the European/Western cynical humanism – where we are all humanists, but only in our own backyards and only when it is convenient and visible – as it exists in and outside of the theatre.

Both plays question the nature of pity and the dramaturgy of suffering, asking its audience:

For whom do we feel more pity?

The productions use competing monologues constructed from a mixture of autobiographical and fictional experiences. The core monologue is performed by a

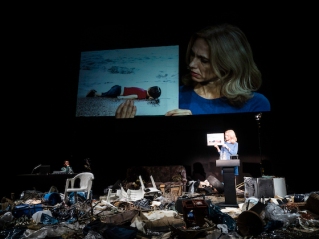

famous white starlet – Ursina Lardi in Mitleid and Els Dottermans in Compassie – and a prologue and epilogue performed by a black actress – Consolate Sipérius in Mitleid and Olga Mouak in Compassie. The prologue and epilogue – the only opportunity Sipérius and Mouak have to speak during the production – make up only about fifteen minutes of the total production time, while the core monologue – a purposefully and clearly white perspective – make up the remaining ninety minutes. Sipérius and Mouak play the role of the witness, remaining onstage throughout the production, watching and listening to their white counterpart’s extended monologues. They remain seated at a small black table throughout the production with a laptop, a small control board for the sound system, camera, and microphone. This well-organized table is placed on the back, left corner of the stage, overshadowed by the piles of garbage covering the stage – which is filled to the point of literal overflow. It is here, amid this empire of trash – discarded lawn furniture, full garbage bags, plastic, and pieces of dirty cardboard – that Lardi and Dottermans perform their monologue… free to move – with great difficulty – around the stage.

“This,” Sipérius and Mouak say in their prologues, “is a play about witnessing.”

However, in sharp contrast to Sipérius, Mouak is not actually a genocide survivor – this aspect of her monologue is fictional. Here, I will briefly return to the question of pity: namely, do we feel more pity for the experiences of the black figure of Sipérius or Mouak (“black is always a statement” explains Lardi) or for the white starlet who has not faced any real struggle or tragedy in their lives.

The production plays with the publicly known of the celebrity. With Lardi and Dottermans, we know (or can easily determine) which experiences are fictional and which are reality-based. However, for Mouak and Sipérius, who are – in comparison to their white counterparts – relatively unknown, which makes it significantly more difficult to determine which aspects of the pro- and epilogue are real, fictional, or exaggerated. Why are we, as spectators, less interested in breaking down the prologue and epilogue than the core monologue? Why is it easier to accept Sipérius and Mouak’s monologues at face value than the Lardi/Dottermans monologue?

Unlike Lardi’s monologue – which is repeated almost word-for-word by Dottermans in Flemish rather than German – Mouak’s monologues (particularly the prologue) is unique. Rau and his team carefully construct two connected but still distinct monologues about the external atrocity and internal racism in Europe. Sipérius describes a linguistic/rhetoric-based racism of the everyday from her childhood – neighbours calling her Bambola, Big Mama, and “a buxom negro girl” – and an interest in her body. Mouak similarly describes similar experiences with rhetoric from her Italian neighbour and how her classmates would touch and mess up her hair to the point her mother had to talk to the teacher (to no avail).

Here already, a certain white European blindness to this insensitivity becomes apparent.

For both women, this was a world without compassion.

The distinctive survivor pro-/epilogues stand in stark contrast to the uncanny repetition of the Lardi-monologue – i.e., the monologue of the white, European starlet. It provides a commentary on the place of the refugee and survivor in the European theatre. Particularly in the wake of 2015, refugee theatre has become a mainstay of the Western European theatrical tradition. However, the danger of

this form of theatre is how reductive it can be, providing an ultimately feel-good evening for the white audience, which reduces the full complexity of the person (and their experiences) to their status as refugee/survivor[iv]. Both Mitleid and Compassie critique European theatre’s reductive obsession with the refugee/survivor, responding to the danger of creating a refugee caricature. The uniqueness of Sipérius and Mouak’s monologues is important because it differentiates among violences and survivor experiences. Looking at violence and tragedy on an individual level, rather than as the byproduct of non-European Otherness – i.e., as something normal and natural outside of Europe’s “enlightened” borders. All the monologues in both productions address violence and atrocity, but it also directly confronts the European audience with their own racism, lack of compassion, and externalization.

Why does the account of Lardi (or Dottermans) seem more tragic than that of Sipérius or Mouak?

Why does a massacre in Central Africa receive less media attention than one in Western Europe?

What are the roots of this inequality of pity and the uneven dramaturgy of suffering?

In stark contrast to the prologue and epilogue, the core monologue is essentially the same monologue in both productions, often a word-for-word translation of the German original (the only real discernible difference is the description of the role reversed Oedipus production – although the Oedipus anecdote is present in both Mitleid and Compassie).

For anyone who is familiar with the original, and this doubling is truly uncanny.

The Ursina Lardi monologue paints a fictional portrait of the eponymous Lardi character – a white, European starlet – who after completing school travels to the Congo in 1994 with “Teachers in Conflict” to teach the less fortunate. In comparison to Sipérius’s straight-forward monologue, Lardi’s long, complicated, and at times scattered monologue is mirrored in Anton Lukas’s stage design – a stage filled with broken furniture (particularly in the Belgian production as a way to mirror how Mouak survived her family’s murder by hiding behind a giant African-style couch), dirty clothes, garbage bags, and a half-burnt sofa. The Lardi-monologue is carefully constructed using a series of interviews that Rau and his production team conducted with NGO-workers and volunteers, in combination with Lardi’s own experiences from a year teaching in Bolivia.

Lardi is an essentially Oedipal figure, moving from blindness to understanding throughout the production. Her recognition of the fundamental failure to understand privilege and complicity of ignorance – a recognition that only emerges in a dream – that she is, in fact, the plague in the city. Itself a commentary on the place of the West and Western European corporations in continuing instances of violence in Africa and the Middle East.

Watching Compassie after having seen Mitleid, one cannot help but realize, it has all happened again: The screams of the raped and murdered are heard across the lake again, Beethoven is blared again, the Rwandan Patriotic Front marches into the refugee camp again, Christoph is saved again, the NGO volunteers are evacuated again, and Merci Bien is murdered again.

The only difference is that this time around we are being told about it from a different – but ultimately interchangeable – white woman.

And there it is…

It could be any white, European actress and it would make no difference.

Lardi’s monologue speaks to a white, Western European experience, the same experience shared by many audience members. We cannot help but recognize ourselves in Lardi and Dottermans: their experience and their blindness.

Even in its absolute specificity, what monologue describes is strangely, uncannily cookie cutter. It is the experience of a specific milieu of white, middle-class, European society, specifically that of the productions’ white, middle-classed audience: i.e., finish school, take time to travel between school and work by

volunteering with an NGO or charity, all while quelling that nagging white, middle-class guilt by building a few houses and helping the less fortunate in a developing country, and (of course) taking a week off to travel.

Within Dottermans’s performance in Compassie and the uncanniness of the repetition, is the revelation that this monologue – Lardi’s monologue or Dottermans’ monologue – could be performed by any white, European actress – regardless of whether she wears a green or blue dress, or whether she is a brunette or blond.

[i] According to the many Germans I’ve spoken to.

[ii] The production has been touring since about July 2018

[iii] According to the Belgians I spoke to.

[iv] The Rwandan actor Dorcy Rugamba – another of Rau’s collaborators – refers to this phenomenon as “the career of the witness”.

I had similar uncanny feeling when I watched 5 Easy Pieces in Hong Kong by the new cast. It’s strange when I saw Winne’s scar and the discovering of another kid’s mom as his doctor, etc etc…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Absolutely! It is also that uncertainty that arrives from within the uncanny where you are no longer quite sure where the already shaky division between the Real and the fictional is now located in the monologues.

LikeLike

Hi there, I don’t know if you’ll see this, but I was looking for resources on mitleid and compassie and ended up here. I wanted to ask what exactly is the difference between two productions? Is it the same piece but compassie as a revival with different cast and a change of word in the title, or are the two completely different performances? I thought of it as former at first but from reading yours I’m getting that you’re implying the latter. Hope you see this and tell me what you think! Going through some difficulty finding english sources on the piece.. thanks in advance 🙂

LikeLike

That is a complicated question, because it both is an isn’t the same production. Olga’s prologue is different than Sipérius’s prologue: Olga’s character is from the DRC, while Sipérius is from Burundi (which means the massacres they talk about happen in different years), while Olga’s character was adopted by a French inter-racial couple and Sipérius was adopted by an all white Belgium family. More importantly, Sipérius is giving a documentary performance in the prologue, while Olga is performing a character based around certain biographic experiences (such as racism she experienced growing up in France and working as an actor with people like Robert Wilson). Both these monologues are performed in French. The epilogues are the same, because the Inglorious Basterds monologue was written by Rau. The main monologue in the Dutch production is more or less a reenactment of Lardi’s monologue in German. They adjust it slightly to talk about some of Dotterman’s experiences working specifically in Belgian and Dutch theatre (such as working with Luk Perceval) that replace the specifics in the beginning of Lardi’s monologue that talk specifically about her acting career. It is interesting because the implication is that any white, female actor could perform this role, but the epilogue and prologue are extremely personal and cannot be reenacted.

LikeLike

Also, there is a forthcoming edition of “Theater”, the journal from Yale that is going to have a few articles that talk about Mitleid/Compassie written in English. It comes in the middle of May (I don’t know if that is too late) and also have the English translation of the German script printed.

LikeLike

Hello, this is a great question, but not a lot has been written about the differences between the two productions. Olga’s opening monologue, while fundamentally the same story has had the details edited (she comes from Congo not Burundi, she was adopted by a white and black couple in France rather than a white Belgian couple, and she worked with Robert Wilson on Jungle Book rather than on a Belgian production of Antigone), the main Lardi monologue also has some specific details changed to specify it (talking about how Dotterman worked with Luk Perceval) and then the actual Congo Monologue is the exact same as in the Schaubühne performance. The epilogue is also the same as the Schaubühne. It is a strange mix of the same and something different. The english text of Mitleid is available in Theater Magazine (Duke University Press) 51:2 and there are a few critical articles about Mitleid in the edition as well.

LikeLike