An Accident

Justice tells the story of a man-made disaster.

On February 20, 2019, in the heart of the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s copper and cobalt mining region between Lubumbashi and Kolwezi – on a stretch of road that runs through the village of Kabwe found about 80km from the mining centre of Kolwezi – a truck carrying sulfuric acid crashed, overturning on top of a bus.

The truck was racing to the Mutanda mine, one of the largest cobalt mines in the world, where the acid would be used to dissolve other metals and metalloids in the extraction process. Mutanda is owned by Glencore, a Swiss multinational commodity trading and mining company active in the region. The tanker, which had overturned on the busy but poorly maintained rural highway, spewed its contents onto those people trapped in and under the bus (essentially, to quote one eyewitness, “dissolving” the victims). Sulfuric acid also sprayed onto nearby cars, drivers, and bystanders, crashing into several houses, and flowed towards the village of Kabwe, destroying homes, the environment, and people in its devastating wake.[1] Beyond the horrifying loss of human life – twenty-one people died, including several children, and the, according to contemporary news reports, an additional twelve were injured (7 according to the statistics shown at the start of the opera), many of whom lost their livelihoods as a result of their injuries. The surrounding landscape was scarred by the acid: crops and water supplies were poisoned and the acid flowed into the village, poisoned the fields, and seeping into the local cemetery, disturbing (and dissolving) the already dead. It is not insignificant for the opera, which works hard to explore the co-existence and clash of what director Milo Rau and librettist Fiston Mwanza Mujila call European modernism and African traditions and temporalities, that by entering the cemetery the acid also disturbed the community’s ancestors.

How could such an accident even happen? Who is responsible for the accident? For the dead? For the injured? For the damage?

Was it Glencore? The multinational that owns the mine the acid was being shipped to? A corporation that prioritizes speed over safety? The corporation who’s mine the truck was barreling towards? A corporation that has, on many occasions, used its considerable weight to manipulate the Congolese government to favour its economic interests?[2] A company that directly benefits from the economic instability in the region (low costs equal high profits)?

However, as Glencore points out in their official statement about the accident, it was neither a Glencore-owned truck that overturned nor a Glencore employee driving the truck. It was a third party or, to use the bureaucratic parlance of the legal teams of multinationals: “After considerable internal review, we decided not to classify and report this accident as a serious human rights incident in our operations, because it involved a third-party contractor.”[3]

So was the truck driver at fault (the only person to be formally charged for their role in the accident)? Speeding down the busy road and crashing into the stationary bus?

Was it the third-party company hired by Glencore who hired the driver who was at fault? This seems what Glencore’s press release hints towards, blaming (without explicitly naming) this third party (the transport company Access Logistics and the unnamed driver) for the accident. Unsurprisingly, we see how the corporation shifts responsibility away from itself. Because although it was Glencore who owned the acid and the mine the acid was being shipped to, acid is stupid and undiscerning. The acid is, in and of itself, blameless. Yet someone must be at fault. Not responsible necessarily for the accident, but for the conditions that put a speeding tanker, filled with sulfuric acid, on that poorly maintained road between Lubumbashi and Kolwezi, at Kabwe.

The difficult reality of the situation is that there are multiple realities – which Rau and Mujila do an excellent job highlighting – that created the conditions necessary for such an accident to happen (and the many similar accidents that happen every year across the DRC and other unregulated mining regions throughout the Global South). The failure of the international community to develop some form of transnational oversight and regulation for multinational corporations, Glencore taking advantage of the lack of oversight and the unrest in the region to cut costs and corners, the failure of the third-party to vet its drivers and its trucks, the failure of the Congolese government to maintain its roads, the local and regional government’s slowness to respond to the crisis and free the people from the bus, a historical situation that normalizes tragedy in the DRC, and many other, even more mundane failures, oversights, and blind spots. Yet when there are so many different elements explicitly at play in a tragedy, it becomes difficult to identify a single responsible party (which is often how judicial systems function). Instead, it becomes a question of where the blame lies and, from a corporate standpoint, blame is good… so long as it doesn’t land on them. So, they steer attention away from the acid spills, mine collapses, fires, and onsite accidents of local employees that inevitably accompany such an industry, and instead open local schools, build hospitals, and engage in other good will projects that both distract the global media and dissuade local whistleblowers.

You catch more flies with honey anyway.

In their press release, Glencore highlights the very loophole that they, and many other multinational corporations, take advantage of in the DRC – very nearly saying the quiet part loud: “Unlike safety incidents, there is not yet a globally established reporting practice for human rights incidents.” It is precisely through such a loophole that the DRC – resource rich, population (and therefore labour) rich, and economically poor – that Glencore and other multinationals active in the region are able to operate as they do, transforming the DRC and towns like Kabwe into what Cameroonian historian and political scientist Achilles Mbembe calls the death worlds of necropolitics. Death worlds are spaces – often in post- and, therefore, neo-colonial places – in which the lives of entire populations are deemed superfluous, worth less than the product it produces (with multinational corporations and the everyday luxuries of the Global North we see this in the dichotomy of the price of cobalt versus that of Congolese lives). Mbembe, without diving too far into this complicated concept in a rather unacademic response to an opera, explains:

“[t]his life [i.e., the life in the death world] is a superfluous one, therefore, whose price is so meager that it has no equivalence, whether market or – even less – human […] Nobody even bears the slightest feelings of responsibility or justice towards this sort of life or, rather, death. Necropolitical power proceeds by a sort of inversion between life and death, as if life was merely death’s medium.”[4]

Glencore – and not just Glencore, many multinational mining companies – depends on the DRC remaining a death world. Necropolitics are – in many ways – the politics of the neoliberalism and globalized Capitalism that such corporations flourish within, and death worlds the ideal means of production for such a system. Such a system operates best within the void created by the long shadow of Western Capitalism, without proper oversight and the connected issues of justice and responsibility (or lack thereof). It is important to note that – as the librettist of the piece, the Austia-based Congolese author Fiston Mwanza Mujila, does in the opera’s program – the accident at Kabwe is just a single example of many similar accidents that happen and are quickly forgotten every year in the DRC: “a forgotten, underplayed event taken from a local paper in a forgotten country” (Mujila, translated by Google Translate).

Justice demands responsibility and responsibility demands care both locally and internationally. Without care (and there is a larger discussion about what care means on both a local and international level), justice becomes impossible because there will be no demand for it.

An Opera

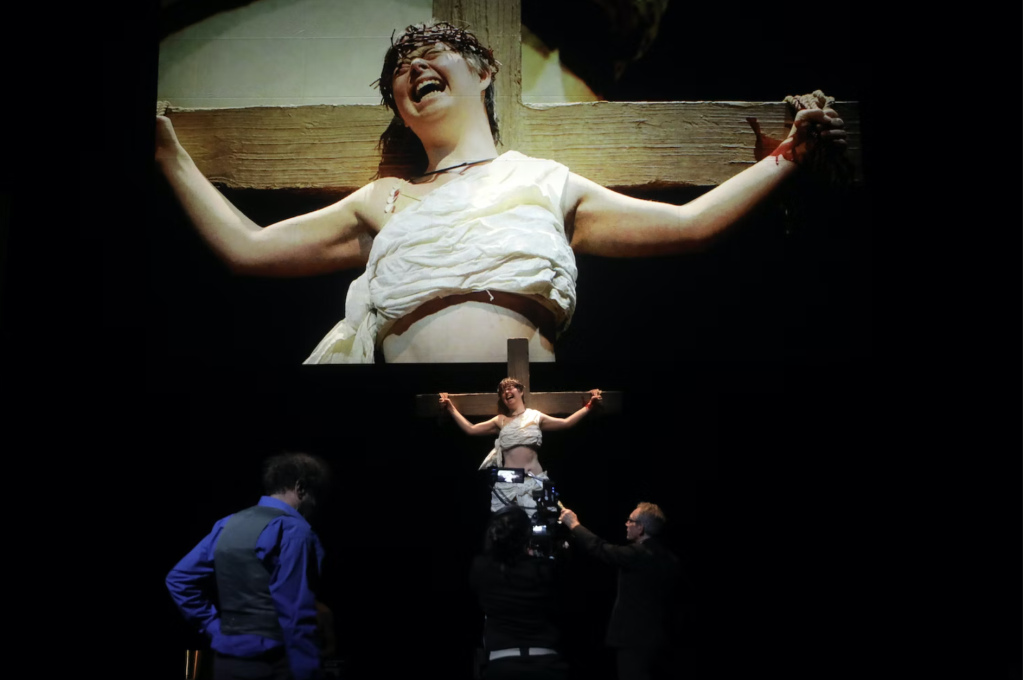

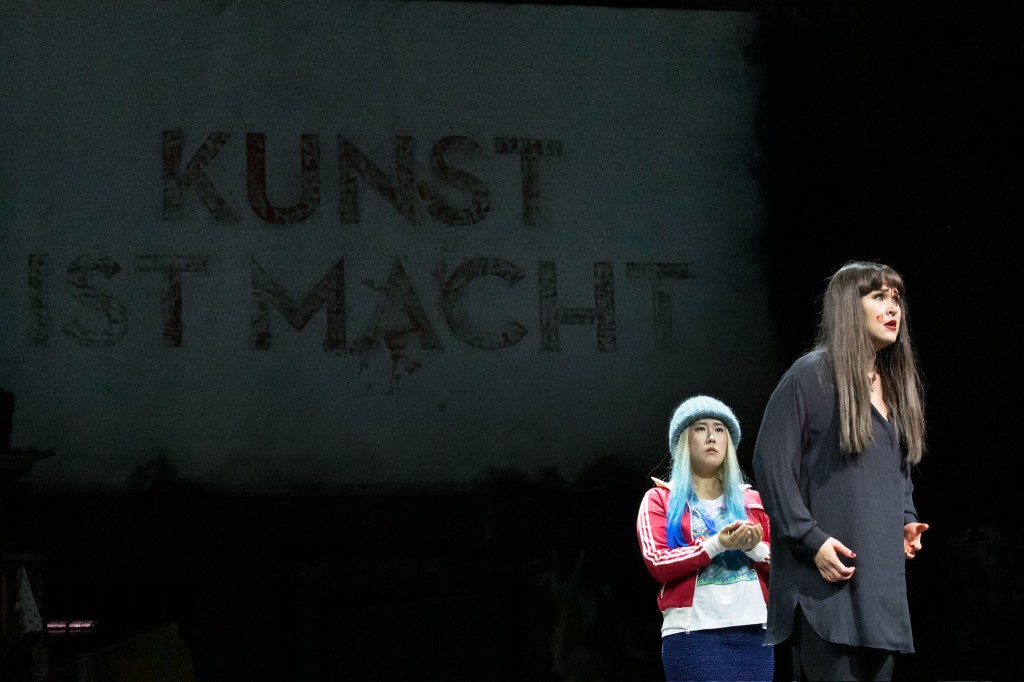

Justice begins here: with this question of justice and responsibility for another forgotten event, in a forgotten space, without proper government and transnational oversight. With the real acid truck accident at Kabwe – using Milo Rau’s favourite convention of a screen hanging above the stage with projections being used to introduce some of the real people impacted by the accident – serving as the production’s grounding base, the opera constructs a secondary, fictional story around the accident’s aftermath and the continued failure of justice for the village.

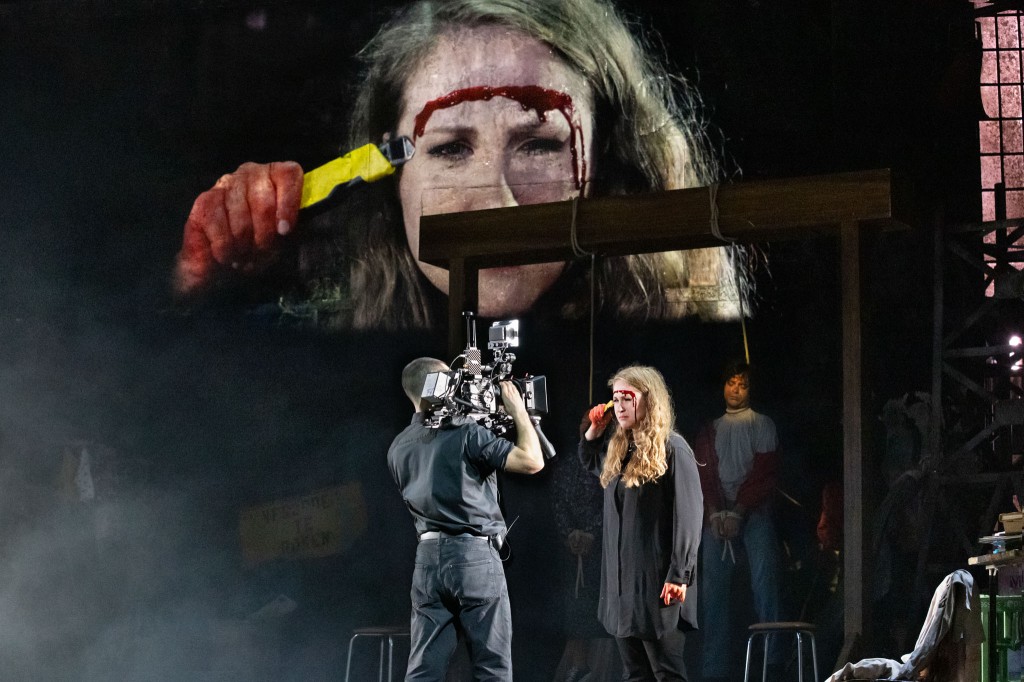

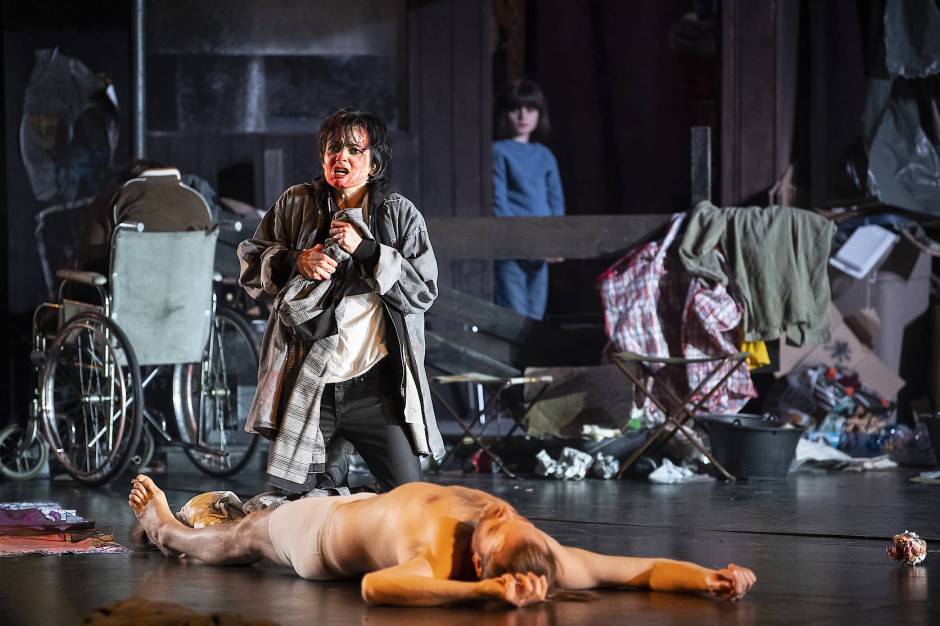

As the curtain parts, the spectator sees for the first time Anton Lukas’s stage design. The red dirt seen in the videos taken in Kabwe covers much of the stage, and upstage left lies the massive, overturned acid truck, surrounded by a gory recreation of the accident’s aftermath for the onstage camera to explore at different points in the opera. Further downstage left, standing almost in the shadow of the accident is the table and chairs of the Swiss conglomerate’s celebratory event. Next to the dinner (downstage left), the truck driver sits on dirty lawn furniture, beer in hand. Stage right, there are a series of black benches that stand like simple church pews or some sort of meeting place that are periodically filled by the chorus.

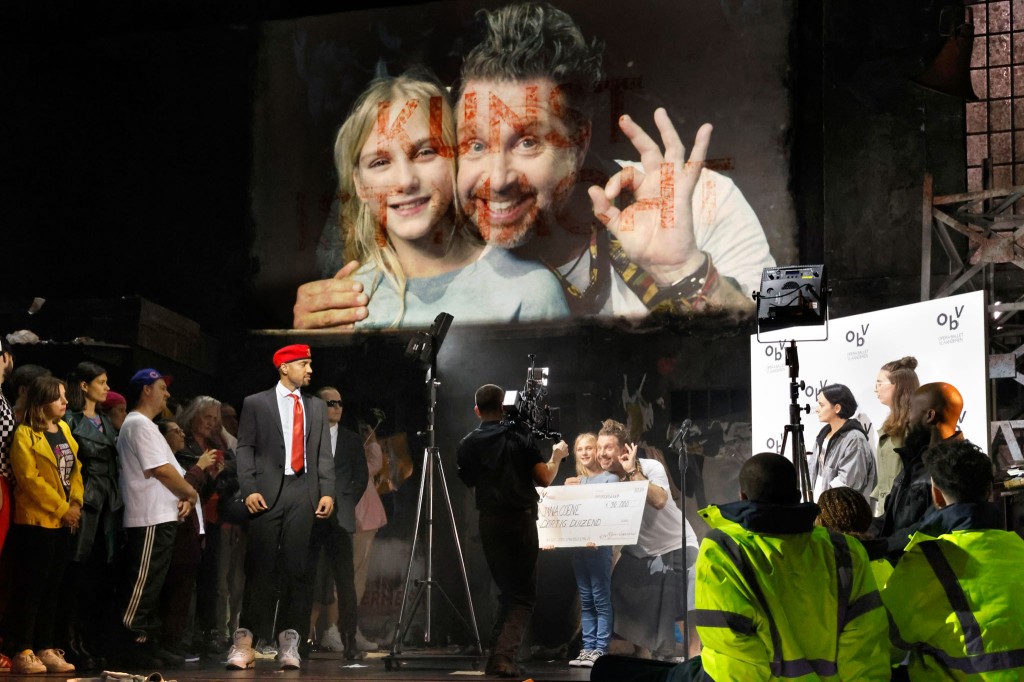

The production begins in Kabwe five years after the accident: A Swiss director of a multinational corporation active in the region and his African American wife, who works with a local NGO, are holding a charity dinner for a mixture of international, national, and local representatives in celebration of the opening of a new school in the city, generously funded by the very mining company responsible for the accident. There is good news for the community, because a coltan belt has been discovered on the nearby hill, thus providing future employment for the entire community. Yet, as the evening progresses, spectres of the past – the victims and aftermath of the accident – become increasingly intrusive and disruptive for the dinner party.

The horror of the accident with acid dissolving people and body parts, flowing into the bustling village marketplace and the community’s cemetery, as well as the continued failure of justice, with a thwarted trial and the company instead paying victims and victim’s families meagre sums of money years after the event intrudes on the celebration. Justice brings the Swiss director, the multinational corporation, and its (and therefore his) economic interests and the morality and intentions of his wife and the NGO she represents into contact with the irreconcilable needs of the local population: for jobs, for money, for education, for a future, but also for justice and closure for the past.

It is in the meeting of these two incompatible temporalities – a living future versus a dead past – that create the opera’s central conflict: justice means holding the multinational corporation responsible for the horrors of the past, which, in turn, jeopardizes the community’s future because its population depends on the company to build schools, hospitals, and provide employment. Yet, for many in the community – and the community itself, whose once vibrant marketplace was the village’s beating heart – it is impossible to simply move past the tragedy as it has (in some cases) left literal scars on their bodies. But as the evening progresses, the situation at the party devolves as victims speak out, spectres of the dead return, the horrors of that day are relieved, and the cry of failed justice becomes overwhelming – to the point of violence.

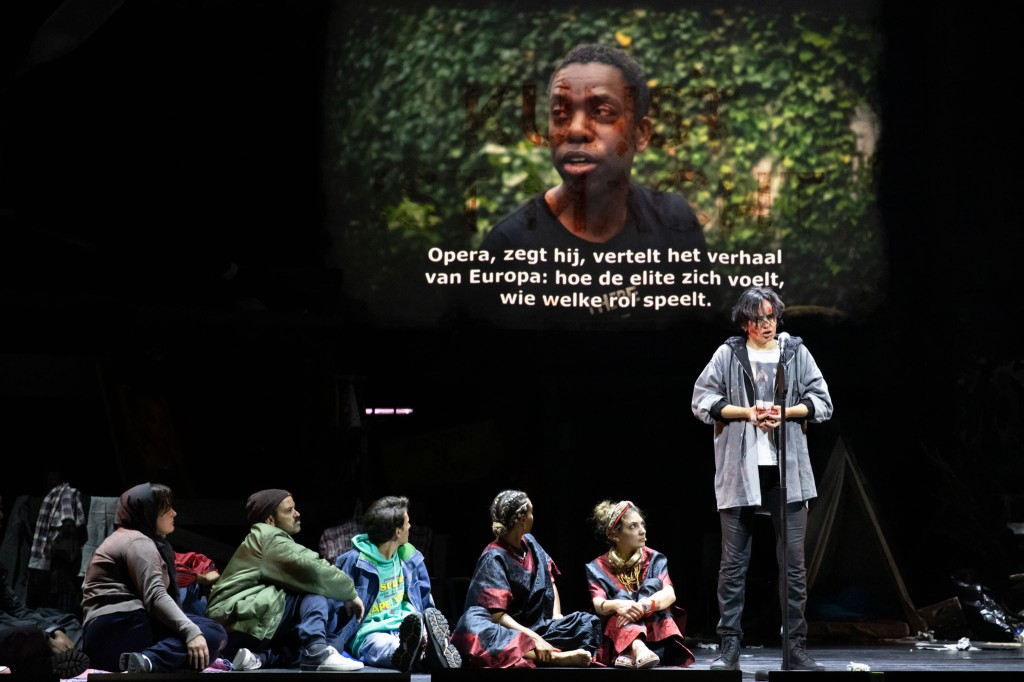

The opera opens in typical Milo Rau fashion: with Fiston Mwanza Mujila speaking. Mujila enters the stage, accompanied by Kojack Kossakamvwe’s guitar, and introduces the opera, himself, and the situation in the region of his birth. He explains why he was compelled to write the libretto, highlighting his sustained connection with the DRC, the country’s long history of violence and occupation by foreign powers, and the unremembered tragedies like the accident in Kabwe. It is only upon Mujila’s instruction – another classic Rau staging – that the massive curtain is pulled back for the opera-proper to begin. Continuing the classic Rau staging first seen with Mujila’s onstage presence, the spectators are then introduced to the cast via the large screen hanging above the stage: projecting the actor, their name, their character, and their background – i.e., where they were born and their connection to opera or the opera’s subject matter.

Early in the production, using the same screen, we are shown a video from the day of the accident. Not the accident itself, but its immediate aftermath. A shaky cellphone video that shows people milling about in shock and horror, melted flesh, sobbing. The video lingers. Running an unbearable amount of time, even though it probably only lasts one or two minutes. The cameraman doesn’t seem to know where to look or what to focus on. The horror is overwhelming. There is a larger discussion to be had about the ethics of using such a video – which is then partially recreated using Lukas’s stage design and the onstage camera later in the performance – but it is undoubtedly effective.

Like many of Rau’s works, Justice consists of five acts: (1) The Riches of the Land, (2) The Billionaire, (3) Sulfuric Acid, (4) Vanishing Worlds, and (5) Farewells. Already the titles tell us a neoliberal story that is both extremely specific to the accident in Kabwe but can be expanded to a story about the colonial West’s and neoliberal Global North’s relationship with the DRC (and other centers of production located in the Global South).

“Act I: The Riches of the Land” – a title representative of the DRC’s status as one of the most resource rich nations on the planet but economically one of the poorest – introduces spectators to the Swiss director’s dinner party. Already in this first act, the interruptions to the dinner party begins with reminders of the horrors of the un-memorialized past. While also taking the time to introduce the central players of this conflict (the business director, his wife, the lawyer who worked on the case, the truck driver, and a mother who lost her daughter), it also introduces the impossible parallels present in the production: first, the clash of local traditions with the cultural norms and expectations of European economic partners and, second, the need for justice versus the need for multinational money. In his libretto, Mujila does something clever, using these parallels to identify the continuation of colonial preconceptions of the people living not just in the DRC but in some mythical, monolithic Africa. “Act II: The Billionaire” explores the experience of Milambo Kayamba (nicknamed, The Billionaire), a young father who was trapped under the bus for hours and ultimately lost both his legs because of the acid as well as his livelihood. This act deals with the issue of reparations for loss of life and livelihood. How, rather than a trial, the company simply paid off survivors and victims’ families with measly – particularly for such a company – sums of money. The act’s title is also indicative of multinationals and their directors, for whom such reparations (paying individuals between $250 and $1000 for their loss of life and livelihood in the years after the event) are merely a drop in the bucket. These corporations can afford to come and go from the region as convenient and for whom loss of life is merely a cost of business.

“Act III: Sulfuric Acid” looks directly at the impact of Western multinational corporations in the region – how the use of sulfuric acid makes the mass mining of resources like cobalt possible, but also devastates the environment (destroying the landscape and seeping into water supplies) – alongside the specific death of a little girl in the accident. Here, we clearly see the connection that Mujila makes between mining and death. Mining consists of people disappearing into the earth and then rising again. People become a sort of walking dead, again connecting the mines of the DRC to Mbembe’s death worlds. It is indicative of the lack of respect for the natural environment that tehse multinational corporations active in the region have, again tapping into the schism between local tradition and European modernity/economic demand. The acid eats away not only the Congo’s environmental and ecological future but its next generation – who not only disappear into the mine but literally dissolve away. “Act IV: Vanishing Worlds” interrogates the European myth of progress, i.e., how through the intervention and invention of technology, innovation, and industry, everything gets better. This act continues to build on the previous act’s concept of European progress, while highlighting that this is a progress that doesn’t even benefit Europeans equally and that actively eats away at the future and stability of the African continent.

The final act, “Act V: Farewells”, begins with an aria of the little girl dissolved during the accident. She calls out for her mother in fear and the dark (her eyes already gone). The act concludes with the Swiss director and his wife fleeing the DRC because of unrest and possible coup in the region. Yet, with the departure of both the company’s director and the NGO his wife works for, there remains a central question: What is justice? In the final scene of the final act, the chorus – dressed in funerary black – returns to the stage to sing about the (im)possibility of justice in “post”-colonial states like the DRC. What is can justice even look like in the aftermath of one Empire and the shadow of another? The librettist, Mujila, also returns to the stage for a prologue. He points to the hollowness of a justice rooted in economic interest: where the monetary compensation given out in response to loss of life is an affordable alternative to a lasting justice rooted in responsibility and long-term change to the system, particularly within those invisible and disposable worlds that stand in the shadow of the Global North.

Between Rau’s staging and Mujila’s libretto, Justice is extremely effective in identifying that a call for justice can exist within contradictory and even incompatible circumstances. The community needs the multinational corporation to build schools, hospitals, and provide employment for the locals – itself indicative of the way in which these multinationals move into regions, forming a monopoly over the mining industry, destroying the local industry and economy, leaving locals without other options for employment. However, the community also needs justice despite the risk associated with such a call: the corporation could leave or, as Glencore did in 2019, close their mines. But the community still needs some form of justice, they still need their voices and experiences to be heard – which is key to Rau’s understanding of justice – as a form of catharsis for the community, but also to create lasting change to the existing system in a way that fairly compensates the victims of such accidents.

An Interlude (I don’t watch operas)

Perhaps you’ve read through the past 3000 words and it’s occurred to you that for post that supposedly responds to an opera, it has said relatively little about the opera itself. As I said in both my responses to Rau’s previous opera, The Clemency of Titus (2021/2023), I don’t feel particularly comfortable responding to operas.

I don’t watch opera. I have seen a grand total of six operas in my entire life (not counting the short excerpts of operas directed by Robert LePage, Romeo Castellucci, and, of course, Robert Wilson I had to watch as part of university courses): The Magic Flute (Staatstheater Kassel), Rusalka (Staatsopera Berlin), some opera I don’t remember (Wiener Staatsoper), The Clemency of Titus twice (the digital release during covid with Grand Théâtre Genève and in-person at Opera Ballet Vlaanderen), and finally Justice. I don’t think I really like opera. I certainly don’t like it the way that many people do, or the way that I love theatre. And I this vein, I recognize there are people out there who love opera and who theatre doesn’t do a thing for.

Don’t get me wrong, I appreciate opera. I am amazed by how much work goes into every part of it and how libretto, composition, and staging have to come together in a way that feels impossible from the outside looking in. Intellectually, from a process and creation standpoint, I see how much work, creativity, and money goes into opera. How much everyone involved from creators to technicians to performers put into the final product.

But sitting in the room and watching it, I don’t really – on an absolutely individual, subjective, non-representative level – get opera. The acting, movement, text, and everything else function very differently in opera in a way that doesn’t translate into my understanding.

So, I don’t feel especially confident responding to operas, particularly their musical elements because I recognize that I am not a particularly musical person. When you read dissertations, articles, and reviews of operas written by people who understand music and music theory, it’s amazing the connections and analyses that they can make. How they can read the different ways the music (both sung and orchestral) interacts with each other. How there is a secondary language within the composition that communicates and tells a story in and of itself.

I cannot do this. I can’t look at a score and see anything (I don’t think I can even read music anymore) or listen to music and make connections with what I’m hearing.

Hèctor Parra, Justice’s composer, is doubtlessly a massive talent and a force of nature. He and his work deserve a more detailed and fair analysis than I can offer, because all I can say is I didn’t get the music. I really enjoyed Congolese guitarist Kojack Kossakamvwe’s performance and the short guitar excerpts he periodically added, but the orchestral music itself made me feel uncomfortable and, at times, annoyed. This isn’t a critique, and it might have been the point of the music being what it was. the situation described in the libretto and staging is also uncomfortable and the music is extremely successful in portraying this same discomfort. I will leave my reading of the composition here because it is about as deep as I feel that I can engage with it. Instead, the rest of this response will look more at thematic elements, because I feel more comfortable engaging with what could be described as more classically theatre elements than the musical elements.

The Injustice of Inequalities

Justice clearly fits within a very specific section of Rau’s directorial oeuvre within a series that the ongoing civil war in the DRC. It is part of a series that consists of Hate Radio (2011), The Congo Tribunal (2015/17/20/…), and Compassion: The History of the Machinegun (DE 2015/BE 2018). Hate Radio and Compassion are repertoire (i.e., scripted, staged, and touring) productions that look at the Rwandan Genocide (Hate Radio) and Burundi Genocide (Compassion) and how the violence of these connected genocides spilled into the DRC as perpetrators fled across the Rwandan border pursued by the Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) (Compassion). The Congo Tribunal – from which Justice directly pulls its subject matter – is a more solution-oriented political action. The Congo Tribunal is a series of one-time tribunals staged with real lawyers, witnesses, perpetrators, bystanders, and experts examining the role multinational corporations in the proliferation of violence in the DRC. The first and best-known iteration of the tribunal – staged by Rau and his IIPM team – took place in 2015 in Bukavu (DRC) and Berlin (Germany). This six-day tribunal was turned into a documentary film that premiered in 2017.

Each of these projects – in their unique performance styles – are interested in exploring unheard voices through witness testimony. Hate Radio draws on eyewitness testimony alongside more traditional documentary sources in its reconstruction of the pro-genocide Rwandan radio station RTLM. Compassion engages in a more complex performative discussion (a theatre-essay) about tragedy in a European theatre space and how this can be expanded to Europe’s social and political pseudo-morality that falls apart in the face of its economic policy. Unlike Hate Radio’s single, real-time monologue, Compassion presents two monologues: the primary monologue is performed by a white actor: the fictional story about her time working with an NGO in the DRC. The second, dramatically shorter, monologue belongs to a survivor (a biographical prologue and epilogue in the original German production), seated at a small table at the side of the stage from where she recalls both the 1993 Burundi Genocide and the racism she experienced growing up in a primarily white community in Belgium. Justice sits between these two productions, using real first-person narratives taken from people impacted by the accident but also creating fictional figures to highlight the role of European corporations in the Global South and the hypocrisy of their rhetoric.

Since the founding of IIPM in 2008, Rau has been interested in unveiling recent traumas (what theatre scholar Frederik Le Roy refers to as unsettled historical moments), i.e., events that can be considered unresolved. Justice is exemplary of the director’s interest in how the conditions of the globalized world are intertwined with unresolved events. The Kabwe acid accident is a prime example of how the visibility of tragedy (like visibility itself) is not an equally distributed resource. Certain tragic and traumatic events – particularly those that happen in the Global North’s neoliberal shadow – are not only allowed to remain unresolved, but it is actually beneficial to the larger system when they are left so. These are situations where Rau’s global realism points out how economic interest trumps the West’s supposed social, moral, and cultural morality.

The Global North’s economic policy operates under a rule of highest profit and lowest (financial) cost – a system that is best for not only multinational corporation, but also Western consumers. When events like Kabwe are left comfortably unresolved and unacknowledged, it allows the system to continue uninterrupted to the benefit of not just multinational corporations, but the Global North as a whole.

Rau’s Central African projects are interested in presenting European audiences with those stories and testimonies excluded from larger Western historical narratives. They present a specifically local, Congolese perspective on the conflict in the region and the impact of Western partners.

Justice almost fits within The Congo Tribunal series. The opera actually uses one of the cases looked at in Schauspiel Zurich’s 2020 iteration of Congo Tribunal. It’s final act also (seemingly) pulls inspiration for its final act from Compassion, building on the earlier production’s “Merci Bien” story (itself taken from a blog written years before the initial production). In Compassion, the “Merci Bien” story consists of the white actor (Ursina Lardi) recalling a dream she had for years after her departure from the refugee camp in the DRC. In this dream, Lardi (the white actor, who performs the primary monologue playing a fictionalized verison of herself) finally realizes that she, like Oedipus (a role she played early in her career), is the cause of the plague in the city. In the final scene of Justice, unrest in the region caused by the lack of response to the accident forces the Swiss director, his wife, and the other white employees of the multinational to evacuate the DRC. Early in the opera, the director’s wife states: “Justice or school? Both are worth it. Both at the same time. Bad luck to you, without justice corruption and chaos will continue” (Google Translate). The statement marks the double bind of existence of the community: its people need the money provided by the multinational corporation, to rebuild, to construct hospitals and schools, to provide employment, to survive. Any sort of real justice puts the relationship with the multinational at stake. Throughout the opera, the wife asks her husband and anyone else who will listen: Why was the trial stopped? It is only as she is about to depart, when she is confronted by the mother of the little girl, that she realizes the bind the community finds itself in. There can be no school if there is justice. And likewise, if there is the threat of justice – the danger of being held responsible for their part in the tragedy – then the multinational will pull funding for the construction of the school, the hospital, and hinder the local populace’s employment in the nearby mine. She, her husband, and the system they both represent are the cause. They are the reason there has been and can be no trial. They are the reason that there can be no justice. In the end, in leu of justice, she too gives the mother whatever money she can – which the mother also demands – and leaves.

This is the same basic principle identified by Brecht: “First bread, then morals.” People living at a subsistence level are too preoccupied with trying to access what they need to survive – money, food, employment, etc. – to worry about the questions of morality, ethics, and justice that slow us down in the Global North.

Conclusion: A Theatre of Witnessing

More explicitly than many of Rau’s projects, Justice highlights that Rau’s is a theatre of witnessing. Not only is the opera constructed around the testimonies of witnesses and survivors, but it is also about having these testimonies heard. The presence of the massive chorus who periodically enter and exit have a clear witnessing function. Their role, like that of the audience, is to bear witness to the survivor testimonies and to watch the horrors that unfold. The screen above the stage brings both the onstage performers, who gaze up at the screen, and the audience into contact with Kabwe and its real-world residents, showing footage collected by Rau and his team during their visits to the region as well as the aftermath of the accident.

These testimonies are performed for the audience in an almost ritualistic way, but unlike the judicial rituals reenacted in Rau’s Congo Tribunal, here we see a memorializing ritual. Mujila compares Justice to a moratory ritual: with the large chorus is dressed in funerary black, what can be described as sung eulogies, and the performance of public acts of mourning. It pulls an invisible event into the spotlight, challenging a very specific European audience (the opera’s white, Swiss, upper middle-class audience – which is a different audience than that of Rau’s usual more classic theatre) to see and respond. Justice grabs hold of an event trapped in a memory void and fills it with the dignity of remembrance and memorialization. Even the video of the aftermath of the accident, while unpleasant to watch, fits into this memorializing process, because what cannot be imagined cannot be responded to and cannot create outrage. The failure of justice depends on apathy on both a national and international level. When the local populace is preoccupied with survival and the international populace is self-interested, justice – as Justice the opera illustrates – becomes impossible. Mujila identifies the current situation in the DRC as one without the luxury of memory.

It is a unmemorialized society.

Thus, Justice acts a memorialization. It refuses to let the accident in Kabwe disappear into the ether. It refuses to let the memory of the little girl killed by the acid fade into obscurity, it refuses to let her mother mourn alone, it refuses to let the man who lost his legs in the accident be forgotten, and it refuses to let the suffering of the community disappear through the clouds of dust kicked up by the meagre sums of money paid by Glencore.

Justice fits into an operatic genre called docu-opera: operas composed specifically around/in response to real-world events. The genre isn’t entirely new, with early examples including John Adams’ Nixon in China (1987) and more recently Ben Frost’s Der Mordfall Halit Yozgat (2022). It sits alongside Congolese choreographer Dorine Mokha (1981-2021) and Swiss musician Elia Rediger’s Hercules from Lumbumbashi (2019), a post-documentary oratorio for mines that also looks at multinational mining corporations in the same region of the DRC.[5] Alongside such projects, Justice exemplifies the exciting potentially of opera to enter the realm of the socially engaged and to respond to the inequalities and injustices of the globalized present.

As an individual project, Justice explores the limitations of such art to provide justice. It, like The Congo Tribunal, can only offer its Congolese participants symbolic justice, but it can pull the event – the accident – out of obscurity, out of the corporate rhetoric of Glencore’s official statement about the accident, and create a demand for something beyond the symbolic. Whether or not this is the justice promised at the beginning of the opera – “there has been no justice, until now” – I’m not sure, but it does create the possibility, even a demand, for real justice.[6]

[1] https://www.vanguardngr.com/2019/02/18-killed-as-acid-truck-bus-collide-in-dr-congo/

[2] At the end of 2019, Glencore temporarily shut down the Mutanda mine, leaving over 3,300 employees without work for roughly two years, and significantly impacting local suppliers and small businesses in the region in a strategic action in response to the Congolese government pushing forward with a legislative reform to impose higher taxes on multinational commodity companies like Glencore; https://sehen-und-handeln.ch/content/uploads/2019/11/congo-summary-2020.pdf

[3] https://sehen-und-handeln.ch/content/uploads/2019/11/congo-summary-2020.pdf

[4] Achille Mbembe, Necropolitics, trans. Steve Corcoran, Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2019: 37-38.

[5] https://www.group5050.net/e-projects/herkules-von-lubumbashi-4yz7g#:~:text=Loosely%20based%20on%20%22Hercules%22%20by,European%20musicians%2C%20song%20and%20dance.

[6] For more information about Justice’s connected crowdfunding action see: https://www.gtg.ch/en/news/crowdfunding-justice-for-kabwe/