The opera opens where it ends. With the Roman emperor Titus’s titular clemency for Sesto, his attempted assassin and friend, and Vitellia, the mastermind behind the plot, Titus’s would-be bride-to-be, the woman Sesto loves, and daughter of the emperor deposed by Titus’s father.

“Let Rome know that I remain unchanged.”

Milo Rau’s The Clemency of Titus [La Clemenza di Tito]…

a birdsong for the world,

a reflection on history as a Wunderkammer displaying the failures and dire misunderstandings that compose human history (there is something to be said of Rau’s early work in reenactment with this framework)…

but this is a review I’ve already written…

In the cold corona winter of 2021, Rau premiered his first attempt at opera with Opera Geneva, La Clemenza di Tito. However, because of a second wave of covid and covid restrictions, the opera had only a digital premiere. The first iteration of Titus sought – in typical Rau fashion – to make the onstage cast representative of the community in which the opera was performed: i.e., Geneva. Although, because we are talking about opera, which has long been considered “high art” (perhaps even some of the highest of high art) in a more antiquated way than even theatre (even the classic city-theatre that Rau works within), it is in some ways more exclusionary and closed in terms of audience access. Who can take three hours off work? Who doesn’t have to work evenings? Who can afford the outrageous prices of tickets? Who feels comfortable in the lush theatre stalls and understands the rituals of watching opera? Considering these questions (which the production comes very close to touching upon), I am hesitant to say that this is a production for the community in which it is performed.

I do not like to repeat myself, but I will run the risk and comment briefly (at least in terms of this blog) on Rau’s restaging of The Clemency of Titus at Opera Ballet Antwerp. However, a more comprehensive reading of the production can be found in the original blog.

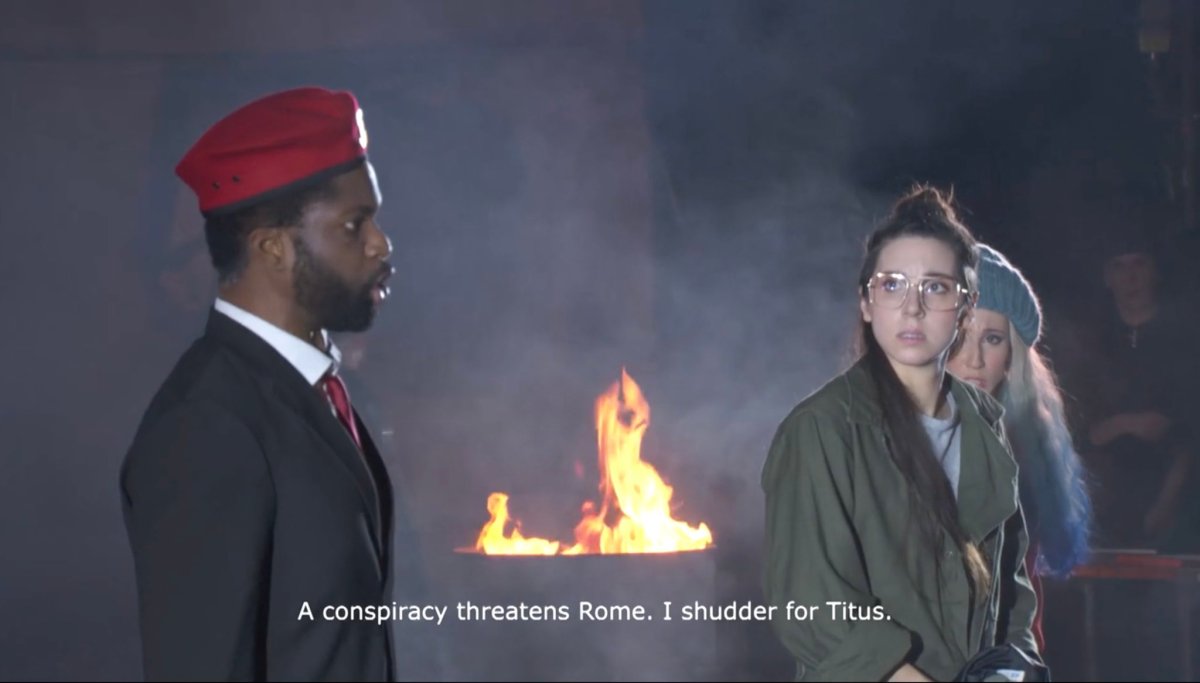

Rau’s production of The Clemency of Titus is without question a beautiful evening of opera. The piece is wonderfully performed by its diverse cast of singers made up of international performers (some of whom are familiar faces at Opera Ballet Vlaanderen, having even performed in previous productions of Titus) and local extras from Antwerp. Designer Anton Lukas creates a striking and effective set, illustrating the stark divide between the elites and the common people. Titus’s palace (or perhaps the senate) is a clean, white gallery in which the artist-emperor’s work is exhibited. On the other side of the rotating stage, we see the dirty, burnt-out ruins of a city, littered with garbage and unhappy people.

By opening with Mozart’s conclusion, we first the museum full of the images taken during the compelled reenactments of famous paintings composed by the performers in each of the opera’s major interactions (a point I will return to shortly). We thus see how the miscommunications, betrayals, revolutions (both of thought and politic), and mistakes of the characters come to fill this museum, which slowly fills throughout the production. Yet ultimately, these failures are – at least for the named characters of Titus, who are privileged, if not noble, citizens of Rome – essentially inconsequential. Even though The Clemency of Titus is about a revolution, it is revolution instigated by elites (specifically, Vitellia, the daughter of the deposed Emperor Vitellio, and Sesto, a young member of one of Rome’s ruling class families). These already powerful instigators are granted clemency, while the extras already executed for the revolution are given no mercy. They are left unavenged. The instigators remain, at their core, unchanged (as Titus declares himself to be at the production’s opening stage) within the safe, clean walls of the gallery.

Rau presents Titus as an artist. The white, bearded emperor uses the suffering of his people as inspiration for his art: the extras are forced into reenacting classic works of art that eventually come to inhabit his museum: The Raft of the Medusa, Liberty Leading the People, and My God, Help Me Survive This Deadly Love. Titus, according to Rau, reflects on the performative mechanisms through which the powerful retain power. What Rau seems to say is that Titus’s clemency – his mercy – is not grounded in care for those under him, but in concern for himself and his position of power and privilege. Live streams are projected above the stage on a white canvas screen with “Kunst ist Macht” [Art is Power] written across it in red paint. An onstage camera and cameraman follow Titus, Vitellia, and other named characters as they cross the stage to interact with each other and extras. The extras inhabit the burnt-out shanty town on the opposite side of the clean, white, art museum, and they become props for the whims of those in power (or who desire it). After they have been filmed or photographed, the extras are violently dispersed by Titus’s bodyguards and their cellphone videos (which we see them making but never actually see) are blocked by the bodyguards.

We are told in the opening when each of the named performers – Titus/Jeremy Ovenden, Vitellia/Anna Malesza-Kutny, Sesto/Anna Goryachova, Annio/Maria Warenberg, Servilia/Sarah Yang, and Publio/Eugene Richards III – are introduced through the projection that the extras are not important. Yet, as Rau seems to point out, Titus is only powerful because of the support of the unnamed mass of people – his community choir. Ultimately, the powerful only retain their power through the people, a point we are routinely shown throughout the opera in Titus’s overt performativity of acts of “care” for the camera that accompanies him.

As Rau explains in the interview printed in the opera’s program:

“It is vital to see Tito as a postmodern man who not only pretends to be powerful, but above all knows that he has lost his power. Only by deploying certain strategies can he continue to hold his power. Presenting yourself as an engaged artist is one such strategy.”

Yet, the opera closes by turning its focus to the extras, thus bridging the gap not only between the elites of the opera and the background characters but also the stars and the extras. Using the massive projection from the beginning of the production to introduce the main singers is now used to introduce extras. It seeks to find commonality. What we find is a mosaic of a contemporary, globalized city, inhabited by people from across the globe. Again, there is a parallel with the operatic institution itself, which, because of the skill and training required of its performers, frequently features international casts. Returning to the program’s interview, Rau explains that the story written into the libretto’s revolution and interpersonal drama is secondary: “The real story is the answer to the questions: who are we? Who are you? Why don’t we look at each other? Why don’t we listen to each other? Why do we not see people in performances, but only extras who are there as decoration?”

Fundamentally – with a few adjustments for its new cast – this is the same production as Opera Geneva’s online one in 2021. Both begin with the removal of the heart of “the last real Genevan/Antwerpian”, both feature a large cast of extras who live in and work in the city with different connections to the opera (as an institution, not Mozart’s composition – although some of them also have this connection), and both act as a commentary on political art and artists. Both use the digital apparatus of projection to first introduce the star singers at the beginning of the performance and the extras at the end.

In both, Titus – unlike in the original text, where Sesto mistakes someone else for Titus in his attempted murder – is seemingly killed by Sesto and brought back to life by a shaman through… the healing power of clay? Honestly, this is a directorial choice that I don’t really understand … perhaps something about Titus being turned into the bust of a Roman emperor? His reputation as Titus – the wise and merciful ruler of Rome – cemented along with his image? Aesthetically, the ritual is an interesting moment. It shows the audience a totally closed off, private moment outside their field of vision that can only be accessed through the projection. This then throws everything we see in the projection from this moment forward into question: is it live or pre-recorded? From this moment on the clay onstage never quite matches the clay in the projection. But why a shaman and shamanistic ritual? And we have to be a bit suspect of the “shamanistic” here, because – I would argue – that it is Rau’s approximation of what this means.

To a certain extent, I question what this restaging tells us about our current societies?

What does this new context tell us that the original did not?

What do we learn about Antwerp that is different than Geneva?

Why did the context need to be shifted other than Opera Ballet Vlaanderen was a co-producer of the original?

And perhaps it is as simple – and for me as unsatisfactory – as that. Opera Ballet Vlaanderen was a coproducer and it economically and ecologically makes more sense to restage such a production with local actors than to drag its actors and its different parts on a tour across Europe. What softly echoes in the back of my head, like a tag on a new shirt that irritates enough to scratch at but not to remove, is that the brush with which Rau paints his image of the globalized cosmopolis is perhaps too broad, too universalizing. We lose the beauty of the specific that can be found in much of Rau’s other work. Yet perhaps this is also the point. The gaps we see between ourselves both within a city – between the rich and the poor, the elites and the citizens, the “locals” and the “migrants” – are not as clear and divisive as we perceive. We are not so different from each other not only within a city, but also between them.

Opera is also a different medium than theatre, which is where I usually work. One in which I find less sure footing. The acting, staging, performance, and mise-en-scène are so differen, and there is less room for Rau to play within the text and insert the socio-political and socio-cultural commentary he is known for. The genre – particularly when we are talking about a classic opera – is more rigid and resistant to the Brechtian alienations, self-reflection, and meta-commentary Rau’s theatre is known for. This is all an extended way of saying – as I think I said in my first review – that I don’t quite have the tools with which to read The Clemency of Titus as a whole.

There are beautiful moments in the production that I love: for example, the use of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Landscape of the Fall of Icarus (1560) as a metaphor for the production. Where the painting’s titular fall is only a small part of the whole. The suggestion of an opera that focuses on those who make up the background – the regular people rather than the emperors and elites – where the struggles and conflicts of the main characters make up just one small part of the picture. Yet with the rigidity of the opera form, this aspiration doesn’t quite occur throughout Titus (in either version), only in select moments. We do see snapshots of the plight of the common people in the background, particularly in the second act (which is, in my opinion, the stronger of the two acts) but the production is unable to break away from the original narrative – neither Mozart composed nor Caterino Mazzolà wrote a libretto for the common people of Rome in Titus (those affected by the eruption of Mount Vesuvius or the Burning of Rome) for Rau to draw upon.

My final note on the production is with a repetition: The Clemency of Titus is a beautiful opera, a more classic and traditional side of Milo Rau than we usually see. It retains the music and structure of the original source material while infusing the mise-en-scéne with the political undertones one has come to expect of Rau.